From a signal-to-noise perspective, the stock market is

an interesting example. A national or global stock market is an

aggregation of large numbers of buyers and sellers of shares in

publicly traded companies. They are described by stock market indexes, which are

computed as the weighted average of a large number of selected

stocks. For example, the S&P

500 index is computed from the stock valuations of 500

large US companies. Millions of individuals and organizations

participate in the buying and selling of stocks on a daily

basis, so the S&P 500 index is a prototypical "big data"

conglomerate, reflecting the overall value of 500 of the largest

companies in the largest stock market on earth. Individual

stocks can fail or fall drastically in value, but the market

indexes average out the performance of hundreds of companies.

A plots of the daily value, V, of the S&P 500 index vs time,

T, for the 75-year period from 1950 through 2024 are shown in

the following graphs.

Each plot contains 75 data points, one for

each year, shown in red. The graph on the left plots the value V

on linear coordinates and the graph on the right plots the natural

logarithm of V, ln(V). There are considerable up-and-down

fluctuations in the value over time that can be related to

historical events: the oil crisis of the 1970s, the tech boom

and bust of 2000, the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, the

trade wars of 2019, and the Coronavirus pandemic of 2020. Still,

the long-term trend of the value is upwards – by 2024

the value was over 270 times greater than its value in

1950. This is basically why people invest in the stock

market, because on average, over the long run, average stock

values go up, usually faster than inflation (which has been

about 3.5% per year since 1950).

The most common way to model this overall long-term increase over time is based on the equation for compound interest that predicts the growth of investments that have a constant rate of return, such as savings accounts or certificates of deposit:

V = S*(1 + R)T

where V is the value, S is the starting value, R is the annual rate of return, and T is time. By itself, this expression would yield a smooth curve, without all the peaks and dips. The values of S and R that result in the best fit to the stock market data (shown by the blue lines in the graphs) can be determined in two ways:

(1) directly, using the iterative curve fitting method, shown on the left above, or

(2) by taking the logarithm of the values and fitting a straight line to the transformed data, shown on the right above.

FitSandPto2024.m

is a Matlab/Octave script that performs both of these

calculations using the data in SandPfrom1950.mat or in SandPfrom1950.xlsx.

When applied to the S&P 500 index data, the rate of return R is about 0.08 (or 8%), but

interestingly these two methods give slightly different results, even

though the exact same data

are used for both, and even though both methods yield the same 8% rate if applied to noiseless synthetic

data calculated from this

expression. How can this be? This difference between methods is

caused by the irregularities in the stock data that deviate from

a smooth line - in other words, the noise - and it is

exacerbated by the large range of the value data V over time and

by the fact that the average return from 1950 to

1987 is lower than that from 1987 to 2024.

You might be wondering how good those data are at

predicting the stock market trends. Over the short term, such

predictions are often not very accurate. For example, the trend

line (blue line) in the left-hand plot predicts that the value

of the S&P in 2024 should be 5000. In fact, in July 2024,

the S&P value

was at an all-time high near 5600, or about 12% higher than the

prediction. This, however, is not out of the ordinary; over the

past 75 years, individual values often have fallen at least that

far above (or below) the best-fit line.

From the point of view of curve fitting, the deviations from a

smooth curve described by the compound interest expression is

just noise.

But from the point of view of the stock market investor, those

deviations can be an opportunity and a warning. Naturally, most investors would like to know how the

stock market will behave in the future, but that requires

extrapolation beyond the range of the available data, which is

always uncertain and dangerous. But still, it's most likely (but not

certain) that the long term behavior of the market (say, over a period of 10 years

or more) will be similar to the past - that is, growing

exponentially at about the same rate as before but with

unpredictable fluctuations similar to what has occurred in the

past.

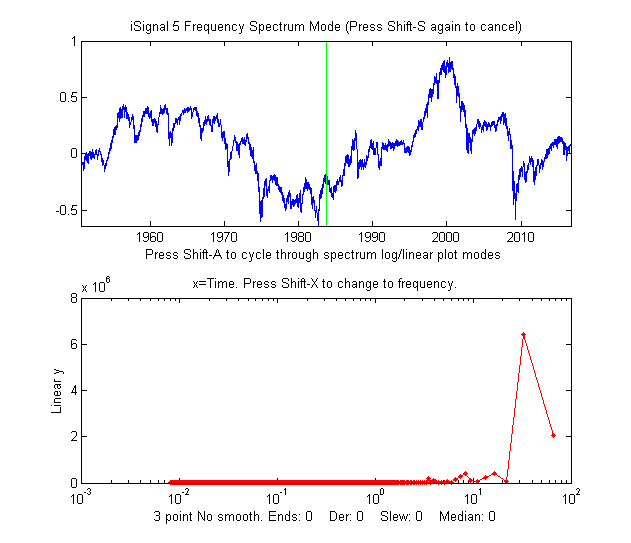

We can take a closer look at those fluctuations by

inspecting the residuals

- that is, subtracting the fitted

curve from the raw data, as shown in iSignal

on the left .

There are several notable features of this "noise". First, the deviations

are roughly proportional to V and thus relatively equal

when plotted on a log scale. Second, the noise has a distinctly

low-frequency character;

the periodogram

(lower panel, in red) shows peaks at 33, 16, 8, and 4 years.

There are also, notably, numerous instances over the years when

there is a sharp dip followed by a slower recovery close to the

previous value. And conversely, every peak is eventually

followed by a dip. The conventional advice in investing is to

"buy low" (on the dips) and "sell high" (on the peaks). But of

course the problem is that you can not reliably determine in

advance exactly where the peaks and dips will fall; you

have only the past to guide you. Still, if the current market

value is much higher than the long-term trend, it will likely fall, and if

the market value is much lower than the long-term trend, it will likely rise,

eventually. The only thing you can be sure of is that, in the

long run, the market will rise. This is why saving for

retirement by investing in the stock market, and starting as soon as possible, is so important: over a 30-year working life, the

market is almost guaranteed to rise substantially. The most

painless way to do this is with your employer's 401k or 403b

automatic payroll withdrawal plan. You can not actually invest

in the stock market as a whole, but you can invest in index mutual funds or exchange

traded funds (ETFs), which are collections of stocks that

are constructed to match or track the components of a market index. Such funds

typically have very low management fees, an important factor

in selecting an investment. Other mutual funds attempt to

"beat the market" by carefully buying and selling stocks in an

attempt to create a return that is greater than the overall

market indexes; some are temporarily successful in

doing that, but they charge higher management fees. Mutual

finds and ETFs are much less risky investments than individual

stocks. "Day traders",

investors who buy and sell stocks and other securities

multiple times over a single day, often do not perform well,

because the market is propelled in the long run by business

cycles, new businesses, and new technologies that do not

change over a single day. Minute-to-minute changes are

mostly noise.

.

There are several notable features of this "noise". First, the deviations

are roughly proportional to V and thus relatively equal

when plotted on a log scale. Second, the noise has a distinctly

low-frequency character;

the periodogram

(lower panel, in red) shows peaks at 33, 16, 8, and 4 years.

There are also, notably, numerous instances over the years when

there is a sharp dip followed by a slower recovery close to the

previous value. And conversely, every peak is eventually

followed by a dip. The conventional advice in investing is to

"buy low" (on the dips) and "sell high" (on the peaks). But of

course the problem is that you can not reliably determine in

advance exactly where the peaks and dips will fall; you

have only the past to guide you. Still, if the current market

value is much higher than the long-term trend, it will likely fall, and if

the market value is much lower than the long-term trend, it will likely rise,

eventually. The only thing you can be sure of is that, in the

long run, the market will rise. This is why saving for

retirement by investing in the stock market, and starting as soon as possible, is so important: over a 30-year working life, the

market is almost guaranteed to rise substantially. The most

painless way to do this is with your employer's 401k or 403b

automatic payroll withdrawal plan. You can not actually invest

in the stock market as a whole, but you can invest in index mutual funds or exchange

traded funds (ETFs), which are collections of stocks that

are constructed to match or track the components of a market index. Such funds

typically have very low management fees, an important factor

in selecting an investment. Other mutual funds attempt to

"beat the market" by carefully buying and selling stocks in an

attempt to create a return that is greater than the overall

market indexes; some are temporarily successful in

doing that, but they charge higher management fees. Mutual

finds and ETFs are much less risky investments than individual

stocks. "Day traders",

investors who buy and sell stocks and other securities

multiple times over a single day, often do not perform well,

because the market is propelled in the long run by business

cycles, new businesses, and new technologies that do not

change over a single day. Minute-to-minute changes are

mostly noise.

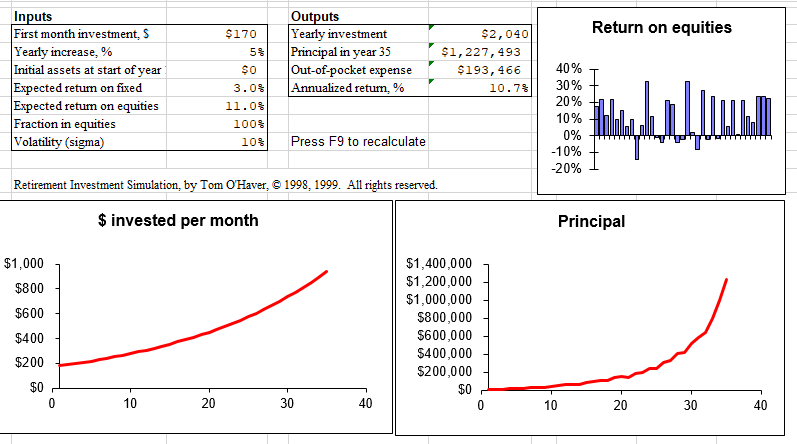

Some companies

periodically distribute payouts to investors called

"dividends". Those dividends are independent of the day-to-day

variations in stock price, so even if the stock value drops

temporarily, you still get the same dividend. For that reason

it's important that you set your investment account to "automatically

reinvest dividends", so when the share price drops, the

dividends are buying shares at the lower price. The S&P 500

index values used above, called price returns, did not

include dividend

reinvestment; the total returns with dividends reinvested

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%26P_500_Index#Versions)

would have been substantially

higher, closer to 11%. (With an average total annual

return of 11%, and starting with an investment of $170 the

first month - that's less than $6 a day - and increasing it 5%

each year, you could accumulate over $600,000 over a

30 year working life, or $1,000,000 if you continued investing

an additional 5 years, as shown by the spreadsheet

graphic on the right). And that's starting at just $6 per

day, about the cost of a fancy coffee at Starbucks. Think

about that the next time you see a line of young people

waiting to order their daily coffee. The hard part is not so

much giving up the coffee as is finding a keeping a steady job

that allows you to make routine automatic contributions to

your retirement account over the long haul. Becoming a

millionaire by the time you retire is possible, but it’s not

exciting; rather, it is slow and plodding.

Some companies

periodically distribute payouts to investors called

"dividends". Those dividends are independent of the day-to-day

variations in stock price, so even if the stock value drops

temporarily, you still get the same dividend. For that reason

it's important that you set your investment account to "automatically

reinvest dividends", so when the share price drops, the

dividends are buying shares at the lower price. The S&P 500

index values used above, called price returns, did not

include dividend

reinvestment; the total returns with dividends reinvested

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%26P_500_Index#Versions)

would have been substantially

higher, closer to 11%. (With an average total annual

return of 11%, and starting with an investment of $170 the

first month - that's less than $6 a day - and increasing it 5%

each year, you could accumulate over $600,000 over a

30 year working life, or $1,000,000 if you continued investing

an additional 5 years, as shown by the spreadsheet

graphic on the right). And that's starting at just $6 per

day, about the cost of a fancy coffee at Starbucks. Think

about that the next time you see a line of young people

waiting to order their daily coffee. The hard part is not so

much giving up the coffee as is finding a keeping a steady job

that allows you to make routine automatic contributions to

your retirement account over the long haul. Becoming a

millionaire by the time you retire is possible, but it’s not

exciting; rather, it is slow and plodding.

To illustrate how much influence stock market volatility fluctuation ("noise") has on the market gains, the Matlab/Octave script SnPsimulation.m adds proportional noise to the compound interest calculation to mimic the S&P data, performs the two curve fitting methods described above, repeats the allocations over and over with independent samples of proportional noise, and then calculates the mean and the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the rates of return. A typical result is:

TrueRateOfReturn = 0.08

Measured

Rate RSD

Coordinate transformation: 0.078

3%

Iterative curve fitting: 0.077

6%

As

you

can see, the two methods don't agree. In this example, the

return calculated by the iterative method is higher, but it could

just have easily been the other way. The fact is that the

standard deviations are fairly large, and the iterative method

always has a higher standard deviation, because it

weights the higher values more heavily, where deviations from

the line are higher, whereas the log transformation method

weights the data more evenly. Even with this uncertainty,

investing in a stock market index fund almost always performs

better in the long run than more predictable investments

such as saving accounts or CDs, which have much lower rates of

return. You can also set the "noise" (in line 5) to zero to

prove that the results would be exactly the same for both

methods, were it not for the up and down fluctuations.

In

investing in the stock market, it's important to focus on the

long-term trends and not to be frightened by the short-term up

and down fluctuations. It's similar to the difference between weather

and climate;

the large and dramatic short-term weather variations

tend to disguise the much smaller long term climate warming

that is slowly melting the icecaps and raising

the sea levels (whether it is caused by human activity or

by natural causes alone or by a combination of both). Everyone

talks about changes in the weather, but the climate changes so

slowly that it is easy to conclude that it stays the same. The

hour hand on the clock is never seen to move.

If

you are young and have many years ahead, keep your investment in

stock funds, which have the best returns. As you get older, you

can gradually shift to lower risk but lower return investments,

such as high-yield savings accounts, certificates of deposit

(CDs), money market accounts, Treasury securities and other bond

funds. Stocks perform better because they profit from new

businesses, technological advancements and improvements in

productivity.

For

a spreadsheet template that allows you to calculate the possible

returns on long-term investments in stock market mutual funds,

see https://terpconnect.umd.edu/~toh/simulations/Investment.html.